I’ve always loved historical fiction, so putting together a full list of titles I’d recommend would make for a very long post. The first novels to captivate me were Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard at secondary school. Soon after, I discovered Dacia Maraini’s The Silent Duchess. To these, over the years, I added books by Umberto Eco, Carol Shields, A.S. Byatt, Hilary Mantel, Rose Tremain, Tracy Chevalier, and many others.

What must historical fiction do, for it to stand out for me? First, it must be beautifully written. I’m very open to experimentation with form – perhaps a result of my own background as a novelist and creative writing tutor. I prize books strong in characterisation, sense of place, story structure and plot development, and other elements of the craft. Second, I’m thrilled when a novel teaches me something surprising. It could be an event central to the whole book, or a small, striking detail. I’m especially drawn to forgotten or silenced perspectives. Third, I value insights and themes that shed light on the past and the present: do they challenge harmful narratives or illuminate legacies we’re still contending with? And fourth, the story must be painstakingly researched and imagined, to possess the authenticity on which everything else rests. That includes a serious attempt at immersing me in the worldviews of the time and place depicted.

If any of this resonates with you, here are seven books I read in the past twelve months that I hope you’ll enjoy. They’re listed in alphabetical order.

Astraea – Kate Kruimink (2024, Weatherglass Books)

This powerful little volume (115 pages) won the 2024 Weatherglass Novella Prize. Set on a ship in the nineteenth century, it’s about a cargo of female convicts destined for Australia. We experience events from the point of view of fifteen-year-old Maryanne. It’s a haunting yet hopeful tale of resilience and camaraderie in the face of misery and brutality. The narration is viscerally immersive, anchored in Maryanne’s raw physical and mental perceptions. Look out for Kate Kruimink, who has already published two other novels.

Costanza – Rachel Blackmore (2024, Renegade/Dialogue Books)

Costanza Piccolomini, the woman at the centre of this novel, was the muse, lover and model of Gianlorenzo Bernini, the leading sculptor of seventeenth-century papal Rome. In a horrific act of violence, Bernini ordered a servant to disfigure her, in the belief she had been unfaithful to him with his younger brother. Basing herself on the facts that have come down to us about Costanza and the other protagonists, Rachel Blackmore has painstakingly reimagined her life. The reconstruction of the all-important social and cultural context is outstanding, and her conjectures about what happened highly plausible, while her portrayal of Costanza’s inner world is empathetic and engaging. The novel tackles enduring themes: double standards, the abuse of power, and coercive control.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain – Victoria MacKenzie (2023, Bloomsbury)

This slim novel brings to life two well known English mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe. They are, respectively, the first woman to have written a book in English, and the first author of an autobiography in English. Victoria MacKenzie imagines their meeting in 1413. She draws on their writings and on her research into the medieval context to offer us vivid portrayals of both. Their personalities and circumstances differ greatly from each other: Julian, a reflective anchoress, and Margery, a chaotic mother of fourteen. And yet, their experiences and spirituality make for a strong connection between the two. MacKenzie balances their alternating voices with a poet’s precision and sensitivity. A luminous reading experience.

Once The Deed Is Done – Rachel Seiffert (2025, Virago)

This is the fifth novel by Rachel Seiffert, whose The Dark Room (historical fiction) was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Once The Deed Is Done opens in March 1945, as the collapse of the Reich draws near. A multi-point-of-view narration gives us access to the thoughts, choices, and personal histories of several inhabitants of a Northern German village. Ruth, a British Red Cross officer, is tasked with supervising and caring for displaced people in a camp the advancing Allied Forces have just set up on the village’s outskirts. Gradually, a dark, shocking secret harboured by some of the villagers emerges. The novel highlights an issue rarely covered in WW2 fiction: the fate of forced labourers during and after the war. With her moving, unsentimental prose, Seiffert poses tough questions about individual and collective responsibility.

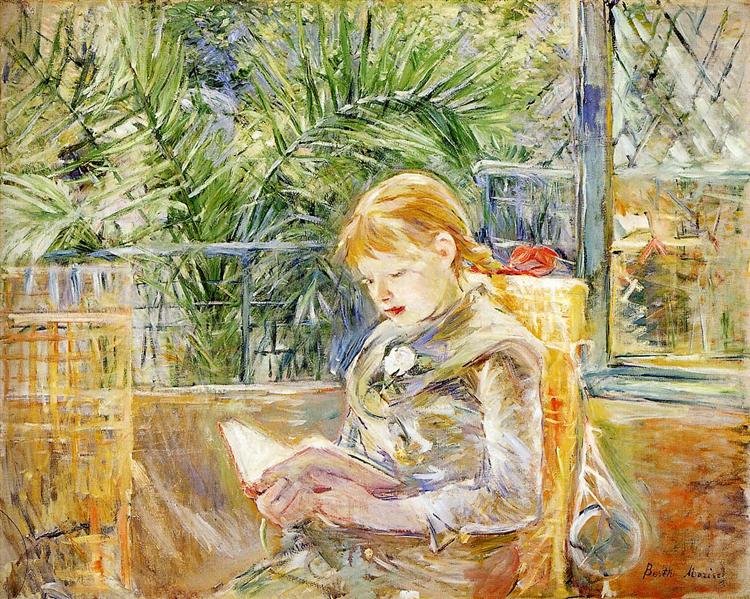

The Painter’s Daughters – Emily Howes (2024, Simon & Schuster) Peggy and Molly Gainsborough are the charming objects of portraits by their father Thomas, one of eighteenth-century England’s most acclaimed painters. Emily Howes turns the two sisters into the subjects of her deeply moving debut novel. Molly suffers episodes of mental confusion from a young age and Peggy instinctively shields her. When the family moves from rural Ipswich to fashionable Bath, hiding Molly’s condition becomes harder. Add to this mix a beguiling composer who enters the sisters’ lives, disrupting their close bond and putting Molly’s fragile sanity at risk. Howes steeps the characters’ thinking firmly in the mentality of the era, rendering their feelings, actions, and dilemmas convincing and deeply affecting. The novel delicately examines themes of devotion, mental illness, sisterly love and rivalry, and other family dynamics. It thoughtfully explores the complex area between protectiveness and control in challenging circumstances, without casting judgment.

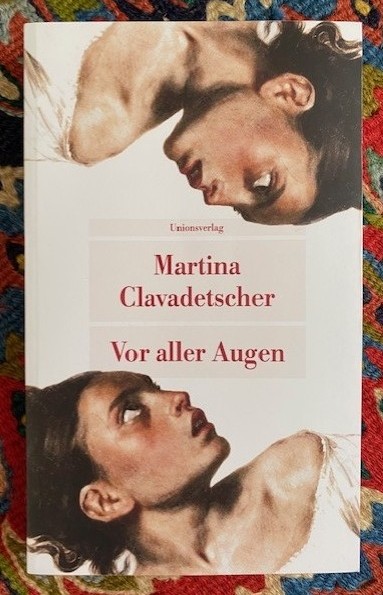

Vor Aller Augen – Martina Clavadetscher (2022, Unionsverlag) I’m afraid this one isn’t available in English yet. Martina Clavadetscher is a well-known author of books and plays, and the winner of the 2021 Swiss Book Prize. In Vor Aller Augen (In Plain Sight), she foregrounds nineteen women portrayed in iconic paintings: from Cecilia Gallerani in Leonardo’s Lady with an Ermine to Victorine-Louise Meurent and Laure in Edouard Manet’s Olympia, from Joanna Hiffernan in James Whistler’s Symphony In White no. 1 to Dagny Juel in Edvard Munch’s Madonna. Clavadetscher not only captures the moments immortalised on canvas, but, above all, lets each protagonist recount her life story in her own distinctive voice. The silenced object of the painter’s (and the viewer’s) gaze thus becomes the active subject, a real-life woman demanding recognition.

And finally, a bonus recommendation: not a novel, but a piece of historical life writing. Fiction can vividly evoke what it was like to live in another era, but so can micro-history and exceptionally well-crafted family memoirs like the one featured below. Originally published in German, it appears in a superb English translation by Jamie Bulloch.

Alice’s Book – by Karina Urbach, trans. Jamie Bulloch (2022, MacLehose Press)

The title refers to So kocht man in Wien!, a bestselling cookbook authored in 1935 by historian Karina Urbach’s Jewish grandmother, Alice. Forced to flee Austria for England in 1938, Alice survived, while her sisters perished in concentration camps. After the war, she discovered that her book had been reissued in 1939 in an ‘Aryanised’ edition: the author ostensibly a German man; and the names of Jewish and foreign recipes germanised. Despite her repeated appeals, the publisher refused for decades to acknowledge Alice as the true author; it returned the rights to her heirs only after being publicly exposed in 2020. In Alice’s Book, the cookbook is symbolic of loss. It offers a powerful vehicle for tracing the devastating impact of Nazi persecution on one Jewish family – dispersed across China, England, and the U.S. – and for honouring Alice’s spirit of resilience, generosity, and hope. It also sheds light on the disturbing reality of companies and individuals that continued to profit from crimes committed against Jews long after the war had ended.

About me: I’m Italian and British, and moved from England to Switzerland a few years ago. I hold an MA in Creative & Life Writing from Goldsmiths College (University of London). My debut novel, That Summer in Puglia, was published in 2018. I’ve just completed the manuscript of my second novel, Habit of Disobedience, set in Southern Italy in the late 1500s. Inspired by true events, this tale of nuns who stood up to the Church explores themes of power, control and female resistance that resonate today.