Speak of accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction, and you’ll find writers agreeing on some things but not on others. “Shoulds” abound. Accuracy, you’ll often hear, is objective: it involves verifiable facts, from dates and places to furniture and dress. Authenticity, by contrast, is somewhat subjective: the reader must perceive the story’s world as faithful to the era in question.

Like many dichotomies, this clear-cut view of accuracy as objective and of authenticity as subjective is an over-simplification. The accurate details that authors of historical fiction work so hard to respect are unavoidably a selection, made from their own perspective and as a function of the story; conversely, readers may query the authenticity of well-documented elements that clash with widely held stereotypes and tropes. This matters because authors’ answers to these challenges lead to differing choices. It’s particularly important with respect to fictional re-imaginings of the female experience: recent decades of scholarly findings into ordinary women’s lives – whose legacy most impacts the present – now provide us with invaluable insights.

I’ve spent years researching and writing Habit of Disobedience, a novel inspired by real-life 16th-century women in Southern Italy. Scouring manuscripts, books, and articles in historical archives and libraries; attending history conferences; visiting museums of all kinds; corresponding with historians, in my search for missing details… You’ll gather my efforts at faithfulness – accuracy and authenticity – were not half-hearted. Still, since the key protagonists of my story are ordinary women, there are too many gaps to fully piece together the micro-history. I’m a novelist and tutor in creative writing, not a historian: my interest lay in attempting to inhabit the past until I could ‘see’ and ‘hear’ the characters in places that today convey only a faint echo of their struggles, joys, fears, and dilemmas. Where history left voids, I found doors I could open to fictional elements: characters and threads that capture people and the heartrending situations they experienced.

It’s the approach that felt right for this novel. The true events that inspired Habit of Disobedience are dramatic, and the fictional yarns I wove through them had to be highly consistent with their contemporary context. I’ve aimed to offer what Stephen Greenblatt expressed superbly in a 2009 article: for my protagonists to ‘carry the burden of a vast, unfolding historical process that is most fully realized in small, contingent, local gestures.’1

There’s an additional reason why I’ve strived for faithfulness: I wanted to give a voice to these unheard women because of their relevance to the present day. The novel highlights their acquiescence in a system they thought they could not change, the areas of agency they carved out for themselves, and the trigger for their resistance. It holds a mirror to our times, without anachronisms. That’s also why I’ve aimed to immerse readers in the mentality of the time (to the extent available to me, five centuries later) – our value system affects how we frame and express our emotions in different eras and cultures.2 The more deeply readers let themselves be drawn into my protagonists’ worldview, the greater their surprise at how much of it persists today in changed forms.

Participants at a recent Women Writers Network discussion felt that most people today still live in a patriarchal society. The impact on women is obvious, but it is, ultimately, negative for everyone. It’s a framework of attitudes, beliefs, behaviours, and rules that most of us, no matter our gender, have absorbed and unwittingly sustain until we recognise them. Historical fiction can shine a powerful light on them.

As authors, we strive for accuracy and authenticity – seeking to shift perceptions, however slightly, away from stereotypes and tropes. In doing so, we can contribute much-needed nuance to the public discourse, making it more inclusive and less polarised.

In the words of Hilary Mantel: ‘What can historical fiction bring to the table? It doesn’t need to flatter. It can challenge and discomfort. If it’s done honestly, it doesn’t say, “believe this” – it says “consider this.” It can sit alongside the work of historians – not offering an alternative truth, or even a supplementary truth – but offering insight.’3

I look forward to telling you more about Habit of Disobedience as soon as it finds its publisher.

[2] The academic field of history of the emotions was eye-opening in this respect, as was Arlie Russell Hochschild’s concept of ‘emotional labour’.

[3] The BBC Reith Lectures. Hilary Mantel’s Reith Lecture 2 – The Iron Maiden. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08vkm52/episodes/player

Image credits:

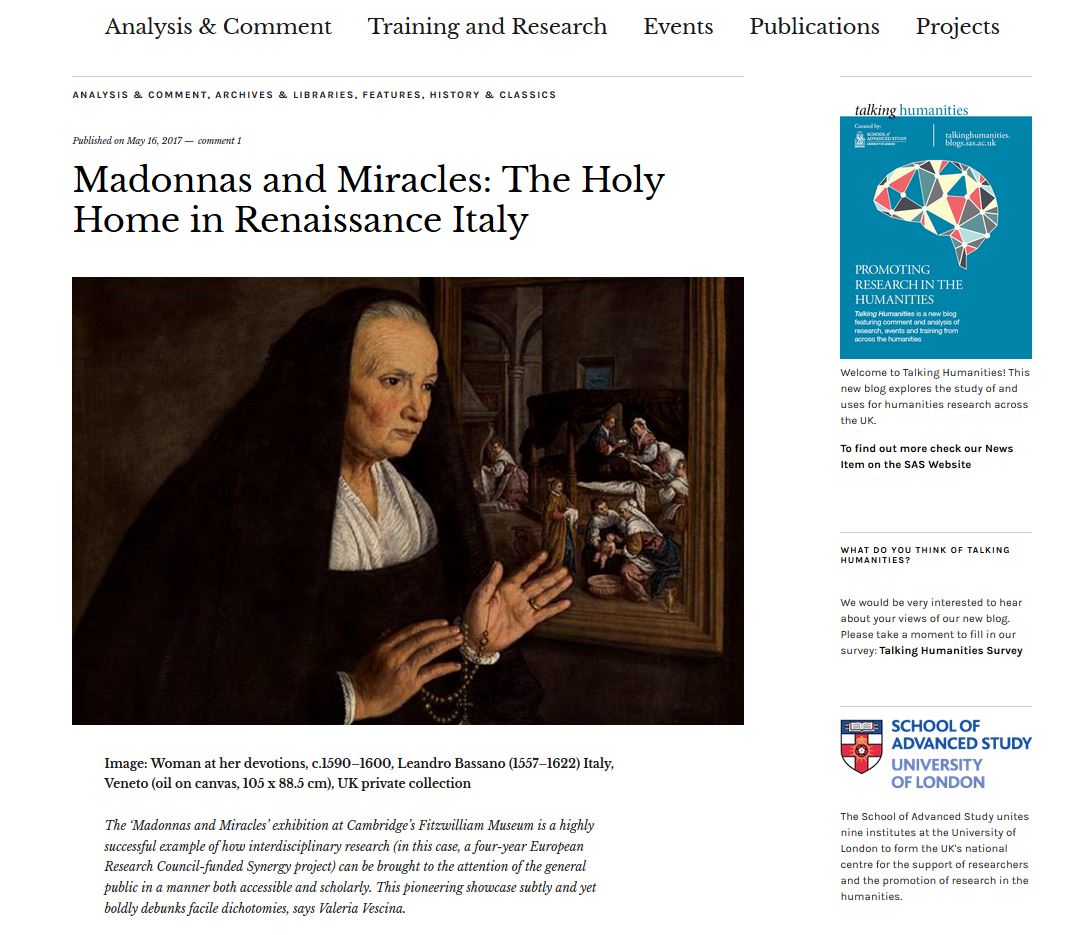

Sofonisba Anguissola’s The Chess Game (1555). Photo by Mortendrak, reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 international license.

Gaudenzio Ferrari’s Birth of The Virgin (1541-43). Photo by the author, taken at the Pinacoteca di Brera.

The second is Orlando Furioso by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), with a libretto by Grazio Braccioli (1682-1752) based on the eponymous work by the Renaissance poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533). See review

The second is Orlando Furioso by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), with a libretto by Grazio Braccioli (1682-1752) based on the eponymous work by the Renaissance poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533). See review  Both works are steeped in the experimentation and questioning of the Enlightenment (and, in Ariosto’s case, in that current of Renaissance humanism which sided with women in the Querelle des Femmes but lost out during the Counter Reformation), but periods of significant cultural ferment have, historically, alternated with others of retrenchment, resulting in historical discontinuities.

Both works are steeped in the experimentation and questioning of the Enlightenment (and, in Ariosto’s case, in that current of Renaissance humanism which sided with women in the Querelle des Femmes but lost out during the Counter Reformation), but periods of significant cultural ferment have, historically, alternated with others of retrenchment, resulting in historical discontinuities.